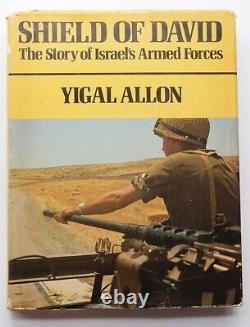

Yigal Alon Signed Autograph Book Shield Of David Palmach Idf Israel Jewish 1970

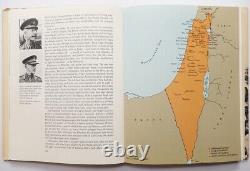

YIGAL ALON HAND SIGNED AUTOGRAPH BOOK. SHIELD OF DAVID: THE STORY OF ISRAEL'D ARMED FORCES. This is the book SHIELD OF DAVID: THE STORY OF ISRAEL'D ARMED FORCES that was written by IGAL ALON Published in Israel in 1970, printed in Israel by Central press Jerusalem and by Japhet press Tel Aviv.

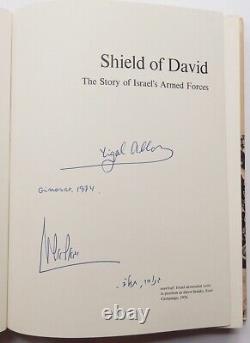

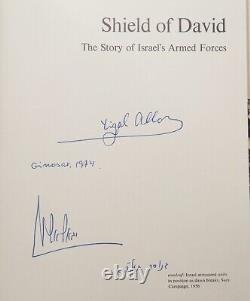

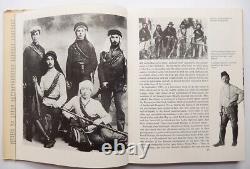

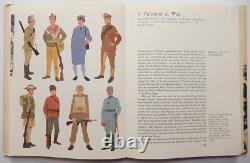

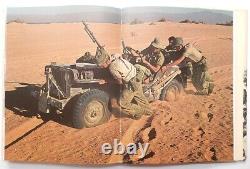

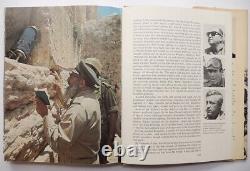

This book is HAND SIGNED by IGAL ALON in English and Hebrew, dated 1974 with the place it was signed and where Alon's lived "Ginosar" (Kibbutz). This is a fascinating and well written book, with plenty of photographs. This book describes the creation of the first military formation in modern Jewish history, and traces it through the six-day war of 1967.

This book is in EXCELLENT CONDITION, like new. Hardcover with the original dust jacket. Please have a look at my other listings.Oldier of the British 6th Airborne Division maintains order outside a baker's shop in Tel Aviv. The 6th Airborne Division in Palestine was initially posted to the region as the Imperial Strategic Reserve. It was envisioned as a mobile peace keeping force, positioned to be able to respond quickly to any area of the British Empire. In fact the division became involved in an internal security role between 1945 and 1948. Palestine had been a British Mandate since the end of World War I.

Under the terms of the mandate, Great Britain was responsible for the government and security of the country. It had long been a stated British aim to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine and between 1922 and 1939 over 250,000 Jewish immigrants had arrived in the country. However, Arab resistance and World War II prompted the British to curtail immigration. The time also saw the rise of the Jewish Resistance Movement, which eventually came into conflict with the British authorities.

When the British 6th Airborne Division arrived in response to increasing terrorist activity, it became involved in internal security, being responsible for cordons and search operations, guarding convoys and key installations. As the situation worsened, the men of the division had to patrol the towns and cities, enforce curfews and deal with rioting by the civilian population. They also protected Jewish and Arab settlements from sectarian violence. This was not without loss to the division and several members were killed and wounded during this time. The end of the British mandate coincided with the post war reduction of the British Army back to peace time levels, and the division's numbers were gradually reduced.By the end of their tenure in Palestine, the division's strength was reduced in real terms, to less than brigade size. In 1948 it was disbanded soon after its withdrawal from Palestine. Contents 1 Background 1.1 Jewish resistance movements 1.2 British 6th Airborne Division 2 Operations 2.1 1945 2.2 1946 2.3 1947 2.4 1948 3 Aftermath 4 Notes 5 References 6 External links Background[edit] In July 1922, the British Mandate of Palestine was created. Under the terms of the mandate, Great Britain was responsible for the government and defence of the country and for the establishment of a Jewish homeland. Then in September 1922, the League of Nations and Great Britain decided that any Jewish homeland would not be formed in the land to the east of the River Jordan.

This instead became a separate country known as the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. [1][2] Encouraged by the British, 265,000 Jewish immigrants, mainly from Europe, came to settle in Palestine between 1919 and 1939.

[3] Arab resistance and violence to this influx of immigrants came to a head in 1937, and the Peel Commission recommended that two states should be formed, one Arab and one Jewish, which would divide the country between them. Then in May 1939, the British restricted the number of Jewish immigrants to 75,000 in the White Paper of 1939. [4] By the end of 1945, Jewish immigration had almost reached the 75,000 White Paper limit. Arab concerns led to the British putting further restrictions on immigration. [5] Even when the scale of the Holocaust became known, the British stance remained the same.

This led to an inevitable confrontation between the British authorities, illegal Jewish immigrants, and militant Zionist groups. [6] It became a widespread belief within the Jewish community that the British were practising antisemitism and were no different from Nazi Germany. [7] However, between 1945 and 1948 a further 85,000 Jewish immigrants, mostly survivors of the Holocaust, entered the country illegally. In 1921, the part-time Haganah was formed and trained as a national army. Most Jewish males and some females were required to join.

After the Second World War, it obtained numerous surplus weapons to equip its members. [9] The Haganah gave priority to increasing the Jewish population by bringing immigrants into the country from Europe. It always attempted to give prior notice of an attack so that any security service personnel in the area could be evacuated. [10] When Axis forces posed a threat to the Middle East in the Second World War, the Haganah organized a full-time, elite force, the Palmach. By 1947, this organization numbered around 2,200 members.

[11] Palmach members were subject to military discipline; many of them had served in the British forces during the war. [12][nb 1] In 1937, a splinter group was formed by those not happy with the Haganah methods. This group was called the National Military Organization in the Land of Israel or Irgun in short.

It launched a campaign of violence against the government in 1944, carrying out several terrorist attacks. [13] By 1945, Irgun had an estimated membership of 1,500. [14] A third group was the Lehi, the Hebrew acronym of "Fighters for the Freedom of Israel", known in the British press as the Stern Gang.

Lehi membership consisted of only around fifty men. It was the only Jewish group that contemplated working with the Italians and Germans during the war, and afterwards assassinated members of the British authorities. [15] By 1946, both the Irgun and Lehi had declared war on Great Britain.

[16] British 6th Airborne Division[edit] Despite its name, the 6th Airborne Division was one of only two airborne divisions raised by the British Army during the Second World War. [17] Before being deployed to Palestine, the division had served only in Europe. It had participated in the Normandy landings in June 1944 and later the Battle of the Bulge in December. After the Rhine crossing in March 1945, it spent six weeks advancing across Germany to the Baltic Sea. [18][19] Men of the Parachute Regiment in Palestine.

At the end of the war in Europe, it had been planned to send the division to Burma to form an airborne corps with the 44th Indian Airborne Division. [20] However, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Japanese surrender, ended the war and changed British plans. The 6th Airborne Division was nominated to be the Imperial Strategic Reserve. Together with a Royal Air Force troop-carrier formation, they were to be located in the Middle East as a quick reaction peace keeping force for the British Empire. 283 Wing RAF had two squadrons of transport aircraft, 620 and 644, available to provide troop transport. By September 1945, the division was en route to the region for airborne training. However, conditions in Palestine were deteriorating. By the time the division arrived, instead of training, it was deployed on internal security. [1] During the Second World War, the division comprised the 3rd Parachute Brigade and 5th Parachute Brigade, both consisting of parachute infantry, and the 6th Airlanding Brigade, composed of glider infantry. [18] However the 5th Parachute Brigade had been sent to India ahead of the rest of the division.[22] So when the division was dispatched to the Middle East, the 2nd Parachute Brigade was assigned to bring them up to strength. [23] In May 1946, after the 1st Airborne Division was disbanded, the 1st Parachute Brigade joined the division, replacing the 6th Airlanding Brigade. The next major manpower development came in 1947, when the 3rd Parachute Brigade was disbanded and the 2nd Parachute Brigade, while remaining part of the division, was withdrawn to England, then sent to Germany. [25] Operations[edit] Further information: Violent conflicts in the British Mandate for Palestine 1945[edit] Still commanded by its last wartime commander, Major General Eric Bols, the division began deployment to Palestine in 1945.

[26] The advance party arrived on 15 September, followed by the Tactical Headquarters on 24 September, then the 3rd Parachute Brigade on 3 October, the 6th Airlanding Brigade on 10 October and the 2nd Parachute Brigade on 22 October. After arriving by sea at Haifa, the newly arrived troops were sent to camps in the Gaza Subdistrict to acclimatize to the conditions, and to regain their fitness after the long sea journey from England. [27] By the end of the month divisional headquarters was established at Bir Salim. The 2nd Parachute Brigade at remained at Gaza, the 3rd Parachute Brigade moved to the Tel Aviv and Jaffa region, while the 6th Airlanding Brigade moved to Samaria.[7] Jerusalem on VE Day (8 May 1945) It was not long before the division became involved in operations, enforcing a night time curfew at the end of October after the railway in the divisional area was sabotaged. [7] On 13 November the British Government confirmed they would examine the conditions of Jews in Europe and consult the Arabs to ensure Jewish immigration, at the time around 1,500 persons a month, was not hindered. [28] Unhappy that the announcement did not go far enough, the Jewish National Council arranged a twelve-hour strike for the next day. Rioting started in Tel Aviv and the Jewish part of Jerusalem, which resulted in the 3rd Parachute Brigade being deployed to patrol the streets for the following five days. [29] The first operation involving the 6th Airlanding Brigade followed two attacks by the Palmach on coastguard stations over the night of 24/25 November.

Palestine Police Force dogs tracked the attackers to the settlements of Rishpon and Sidna Ali. In the following cordon and search operation, the police were stoned by the inhabitants, and the soldiers on the cordon had to prevent reinforcements from other settlements reaching the villages. The next day, 26 November, the police were involved in hand-to-hand fighting with the villagers and eventually withdrew, calling on the brigade to enter the settlements and enforce law and order.Leaving some men behind on the cordon to hold back the estimated 3,000 crowd, the remainder of the brigade entered the settlements. Here they carried out several baton charges and for the first time used tear gas to disperse the crowds. In the cleanup operation, 900 persons were later arrested. [30] Near the end of the year, over the night of 26/27 December, several attacks were carried out by the Irgun on police stations, Palestine Railways installations and one British Army armoury. The 3rd Parachute Brigade again enforced a night time curfew on Tel Aviv.

Then on 29 December, it took part in Operation Pintail, the search of Ramat Gan, for Irgun members involved in the attacks. The brigade questioned the 1,500 inhabitants, arresting eighty-nine. [31] 1946[edit] The first mission of 1946 was Operation Hebron on 8 January. This time the objective was the cordon and search of the town of Rishon LeZion by the 3rd Parachute Brigade and the police, during which fifty-five suspects were taken into custody.For the rest of the month, the brigade was involved in several smaller operations. In Operation Pigeon on 30 January, they searched the Shapira district of Tel Aviv.

[31] Tel Aviv 1946, Jewish civilians waiting to be interviewed by police and army officers, guarded by a soldier from the Parachute Regiment. On 5 March Major General James Cassels took over command of the division. [32] The next action involving the division was over the night of 2/3 April, when units of the Irgun attacked railway installations in the divisional area. While one attack on the Yibna railway station and police post was in progress, a mobile patrol from the 9th Parachute Battalion arrived, detonating a mine while crossing a bridge. Three of the patrol were wounded, but the others took off after the saboteurs.[33] Reinforcements arrived from the 5th and 6th Parachute Battalions. In the morning, tracks of around thirty men were discovered leading away from the area. A spotter plane later located the men and directed a section of the 8th Parachute Battalion to intercept them. After a small battle, fourteen of the saboteurs were wounded and twenty-six prisoners taken. [34] In March the 1st Parachute Brigade joined the division.

The 6th Airlanding Brigade left the division on 13 April, but remained in Palestine as the 31st Independent Infantry Brigade. [35] This reduced the division's manpower by around twenty-five per cent as the strength of the airlanding brigade had been almost equal to that of two parachute brigades combined.

[36] At 20:45 on 25 April, the Lehi carried out an attack on a divisional car park in Tel Aviv. On that night, the car park was guarded by ten men from the 5th Parachute Battalion. The attackers, around thirty men, established a fire base in a house overlooking the car park. The attack began with a bomb thrown into a guard tent. Gunfire was directed at all of the soldiers in the area, then twenty of the attackers stormed the car park.

Once inside the compound, they entered the guard tents, killing four unarmed soldiers and looting the rifle racks of weapons. Another two off-duty soldiers, responding to the attack, were killed approaching the car park. In total, seven men from the division were killed. [37] This was the first deliberate attack by any group targeting the British Army, which had not established defences against any form of assault.

During the following day seventy suspects were rounded up, but no evidence of their involvement could be found. In response to the attack, the British imposed a road curfew from 18:00 to 06:00 each night and all cafes, restaurants and public entertainment venues in Tel Aviv were closed between 20:00 and 05:00. [38] However this was not enough for some members of the division, who attacked Jewish houses in Qastina and Be'er Tuvia, injuring some of the occupants. Those involved were later punished by the British Army.

[39] Attacks on the security services had increased to a level that on 19 June all ranks were ordered to be armed at all times on or off duty, and to travel in pairs during the day and in threes at night. [40] Near the end of June the division received orders for Operation Agatha, the arrest of Jewish leaders "suspected of condoning" or being involved in sabotage or murder of civil and military personnel. Agatha was a nationwide operation involving not only the 6th Airborne Division but the Palestinian Police Force and all other army units in the country. Secondary objectives were to gather intelligence and arrest any members of the Palmach that could be found.

[41] Operation Agatha started at 04:15 on 29 June. The 2nd Parachute Brigade was responsible for Tel Aviv, the 1st Parachute Brigade for Jewish settlements around Ma'abarot and the 3rd Parachute Brigade for those around Givat Brenner. [42] The operation ended on 1 July after 2,718 suspects had been arrested. Many had no connection to the resistance movements and were instead arrested for harassing the searchers or for refusing to give their names when asked. [43] The 6th Airborne Division alone arrested 636 persons, 135 of them for being suspected Palmach members and ten were Jewish leaders. [44] The King David Hotel after the attack The next major incident was on 22 July, when the British administrative and military headquarters located in the King David Hotel were bombed. No members of the division were directly involved, but the Royal Engineers of the 9th Airborne Squadron were called in to take charge of the search for survivors and secure the part of the building left standing. Over the next three days they located six survivors and the bodies of ninety-one victims.[45] To assist in the search for those responsible, the 8th and 9th Parachute Battalions moved into Jerusalem on 23 July. [46] The British response to the bombing came on 30 July, when the division carried out Operation Shark. Believing that the bombers were being sheltered in Tel Aviv, every dwelling and building was searched for members of the Lehi and Irgun, and the population questioned.

[47] During the operation, a cordon surrounded the city and a curfew was imposed on its inhabitants. The division's three parachute brigades were each given one quarter of the city to cordon and search while the fourth quarter was the responsibility of the 2nd Infantry Brigade, attached to the division for the operation. [48] Over four days each brigade questioned around 100,000 people, and 787 were detained for further questioning. During the searches, five arms dumps were found, containing four machine guns, twenty-three mortars, 176 rifles and pistols, and 127,000 round of ammunition. [49] The division's next operations were Bream and Eel, searching for arms in Dorot and Ruhama, by the 3rd and 8th Parachute Battalions, and the 9th Airborne Squadron Royal Engineers.

The two villages were cordoned at dawn on 28 August. Over the next six days the settlements were searched, during which a large quantity of assorted weapons, including heavy machine guns and mortars, were found. [50] Over the remaining months of the year the division carried out patrols of the rail and road networks, which were being mined.

Some of the mines killed men from the division attempting to disarm them, until orders were issued to blow the mines up rather than disarm them. [51] Then on 2 December a road mine killed four men from the 2nd Forward Observation Unit (Airborne). [52] A change in command occurred on 13 December when Major General Cassels left the division and was replaced by Eric Bols, now commanding the division for the second time. [53] 1947[edit] Further information: 1947-48 Civil War in Mandatory Palestine and United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine Between 29 December 1946 and 3 January the division's brigades carried out seven search operations in Tel Aviv, arresting 191 people. [54] On 2 January several attacks were made on roads in the division's area.

One attack wounded eight men of the 4th and 5th Parachute Battalions. Another attack on the same day was carried out by the Lehi against the 1st Parachute Battalion headquarters in Tel Aviv, killing a Jewish policeman and wounding two soldiers and another police officer.

[55] Then on 18 January the 6th Airborne and 1st Infantry Division swapped locations, the airborne division now assuming responsibility for the north of the country. [56] Although it remained part of the division, the 2nd Parachute Brigade was withdrawn to England on 24 January. [57] Upon their arrival in the north, the 1st Parachute Brigade assumed responsibility for the District of Galilee, and the 3rd Parachute Brigade for the District of Haifa, [58] with division headquarters located in the Stella Maris Monastery. [59] The 1st Parachute Brigade also took under its command the Transjordan Frontier Force and a battalion of the Arab Legion to cover their large area. [60] In the north the division was mainly responsible for the security of the port of Haifa, the largest in the country, where they protected oil installations, the Mosul-Haifa oil pipeline and prevented illegal immigrants from landing on the coastline.

[60][nb 2] On 31 January it was announced that all non-essential British civilians were to be evacuated, due to the worsening situation. [62] The evacuation took place from Haifa between 5 and 8 February, under the control of the 8th Parachute Battalion and the Royal Navy. [63] Men of the 6th Airborne Division look at the assorted weapons, ammunitions and equipment discovered in the Jewish settlement of Doroth near Gaza.

On 4 May a group of around forty men carried out the Acre Prison break, releasing forty-one Jews and 214 Arabs. At the same time a mortar attack was carried out on the 2nd Parachute Battalion's camp, as a diversion. [64] The first unit to reach the prison was a platoon from the 1st Parachute Battalion, 35 minutes later.

Other men from the battalion and some divisional units were bathing in the sea a short distance from the prison. A truck load of escaping prisoners opened fire on one unit's armoured car.

The escaping truck then reached an improvised road block set up by some bathers and crashed under fire. [65] The division's bathing party killed four attackers, four Jewish and one Arab escapee, and recaptured thirteen Jews. The bathers had eight men wounded during the short battle.

While this was going on, the 1st Parachute Brigade was establishing a cordon around Acre and the surrounding area but no further escapees were caught. [66] The next attack was on officers from the 9th Parachute Battalion on 28 June. The officers were dining at a restaurant when two men of the Irgun approached and fired machine guns through the windows. One officer was killed outright while several others were wounded.

[67] On 19 July two police officers on patrol in Haifa were shot in the back and killed. The following day the 3rd Parachute Brigade cordoned the area and imposed a night time curfew, which was not lifted until 30 July.

[68] Leadership of the division changed again on 19 August, when Major General Hugh Stockwell was given command. [69] In October the British War Office announced the division would be reduced by one brigade.

The 3rd Parachute Brigade was disbanded, leaving the 1st Parachute Brigade in Palestine and the 2nd Parachute Brigade in England. [70] The 1st Parachute Brigade assumed responsibility for Haifa and to cover all its commitments the 2nd Battalion Middlesex Regiment was attached to the brigade. [71] At a meeting on 29 November, the United Nations General Assembly decided to end the British Mandate on 1 August 1948.Palestine would be partitioned into separate Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem becoming an international city. [72] The Jewish state would have fifty-six per cent of the land with a population of 490,000 Jews and 325,000 Arabs, while the Arab state would have 807,000 Arabs, but only 10,000 Jews.

The population of Jerusalem would be around 105,000 Arabs to 100,000 Jews. [72] On 13 December trouble came from another quarter, in the town of Safed, opposite the Golan Heights. Fighting had started between the Arab and Jewish inhabitants. The police requested help from the army and a company from the 8th Parachute Battalion was assigned the task. Arabs fired at the British unit on 21 December without causing any injuries. [73] 1948[edit] Further information: 1948 Palestine war Arab irregulars in Palestine, 1947 Tension in the Golan Heights area remained high and on 9 January the Jewish settlements of Dan and Kfar Szold were attacked by Arab irregulars from the Arab Liberation Army, who crossed the border from Syria. The division responded by immediately sending a troop of armoured cars from the 17th/21st Lancers to each village. By the afternoon the 1st Parachute Battalion had joined the battle and air support from the Royal Air Force was called in. The battle ended with the Arabs withdrawing; their casualties are not known.Nine Jews were killed or wounded by the Arabs, the British troops uninjured. [74] To assist in controlling the region, an ad-hoc formation called Craforce was established. Under the command of the division's commander, Royal Artillery Brigadier C. Colquhoun, were the division's artillery, the 17th/21st Lancers, the 1st Parachute Battalion and the 1st Battalion Irish Guards.

[75] Craforce became involved with breaking up attacks between Arab and Jewish forces. The Arabs did not directly attack the British, but did engage them when British attempted to intervene in an attack on Jewish settlements.

[76] In February the Arab Liberation Army, under the command of Fawzi al-Qawuqji, was estimated to be around 10,000 strong. It was believed around 1,000 volunteers from neighbouring Arab states joined each month.

[77] On 18 February it was announced that the 6th Airborne Division would be disbanded when they left Palestine. [78] The 1st Parachute Brigade handed over Haifa to the 1st Guards Brigade on 6 April. [79] Gradually the division's units left the country.The division's last units, comprising part of divisional headquarters, the 1st Parachute Battalion and the 1st Airborne Squadron Royal Engineers, departed on 18 May. [78] Aftermath[edit] Further information: Arab-Israeli conflict David Ben-Gurion reading out the Israeli Declaration of Independence Since the end of the Second World War, the campaign in the British Mandate of Palestine had cost the British 338 dead. [80] The numbers for the 6th Airborne Division between October 1945 and April 1948 were fifty-eight men dead and 236 wounded due to enemy action, a further ninety-nine men died, from causes not associated with a hostile act. [81] During their searches of Jewish and Arab settlements, men from the division had located 99 mortars, 34 machine guns, 174 sub machine guns, 375 rifles, 391 pistols, 97 land mines, 2,582 hand grenades and 302,530 rounds of ammunition. [82] In February 1948 the 2nd Parachute Brigade moved from England to Germany, becoming part of the British Army of the Rhine.

[83] The 6th Airborne Division was disbanded in April 1948, shortly after their return to England, leaving the 2nd Parachute Brigade as the only brigade-sized airborne formation in the British Army. [84] On 14 May, the day before the end of the British mandate, David Ben-Gurion, chairman of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, announced the establishment of the state of Israel in parts of what was known as the British Mandate of Palestine. The announcement was the catalyst for the start of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War.[6] "The Kalaniots" The 6th Airborne Division In Palestine (Utrinque Paratus) When the war in Europe ended in May 1945 the 6th Airborne Division were at Wismar on the Baltic. The 6th were tasked for operations in the Far East but with the surrender of Japan, these arrangements were revised. On September 21st 1945, divisional and tactical HQs of the 6th Airborne Division flew out to Egypt and established themselves near Gaza, to be followed by the rest of the Division between September and November. Palestine in 1945 was administered by Great Britain under a mandate from the League of Nations dating from 1923.

The 1939-45 war had overshadowed the'Palestine Question' and apart from Arab extremists and the Jewish dissident groups, the vast majority of Jews and Arabs were too busy to pursue it. Many Jews had fought in the British Army, so by 1945 Palestine Jewry had acquired a great deal of battle experience-and also one way or another, a considerable supply of arms and ammunition. Of all the burdens cast on British soldiers by politicians, Palestine was one of those heavy burdens and into this situation came the 6th Airborne Division, as open minded a body of troops as any in the world, who had many Jews in their ranks in the battles against Nazi Germany.Even as the battalions moved into tented camps south of Gaza in 1945, Jewish newspapers were describing them as'oppressors' and'Gestapo' come to persecute the Jewish people. There were a number of Jewish military or para-military formations.

National Army and closely linked to Hagana was Palmach-the spearhead group. This force was used by the Jewish authorities for acts of sabotage. There were two other dissident groups who answered to no authority but their own leaders. These were Irgun Zvai Leumi (IZL) and the smaller even more extreme Stern Gang. The 3rd Parachute Brigade was sent to Lydda District, which included Tel Aviv; the 6th Airborne Landing Brigade went to Samaria, and the 2nd Brigade remained at Gaza.

November 13th the white paper on Palestine was published. It dodged the issue of a Jewish homeland causing bitter disappointment among the Jews. A 12-hour strike and rioting was called for in. The Palestine Police could not cope so the 8th Battalion Parachute Regiment was called in.

As violence spread, the whole of the 3rd Brigade became involved and order was not restored till November 20th. C Company, 8th Parachute Battalion, veterans of the European war, had been standing by in a nearby barracks all day. They came in four slowly moving, uncovered 3-ton vehicles with horns blaring and the men displaying their bayonets and the signs with the message in three languages,'Disperse or we fire'. The crowd dissolved at speed. The soldiers then leapt out to complete the clearance of the square.

It was all achieved with no injuries to either side. The Tel Aviv riots heralded a conflict between the 6th Airborne and Zionism and in a thankless role the Parachute Division earned them the nickname of'Kalaniot' -the red poppy with the black heart. On the night of April 25th 1946, members of the Stern Gang attacked a lightly guarded military car park and deliberately murdered seven soldiers of the 5th (Scottish) Parachute Battalion.

The'car park murders' were shocking and destroyed the goodwill and trust, which had existed among the British troops and the populace up till then. Far worse outrages were committed later on, which is presumably what the terrorists wanted.

Off duty soldiers still walked out unarmed to avoid looking warlike and not to upset the newly settled Jews. For the first time outrage acquired true meaning. All this time the terrorist campaign continued.Frequently towns and villages had to be searched for wanted men or arms and photographers would be on hand to provide the New York newspapers with fresh evidence of British'brutality'. Every time a British soldier is killed in Palestine,' wrote the American playwright Ben Hecht,'I make a little holiday in my heart'.

Such was the Zionist propaganda machine, but always the cycle of events came back to cordon and search. The reinforced 6th Airborne, now with the 1st Parachute Brigade under its command, with 5 brigades, three-armoured car regiments and supporting units, searched the whole of Tel Aviv, a city of 17,000 people. By now the future of Palestine was before the United Nations and a new danger threatened Zionism-the Arabs. Hagana and Palmach turned their energies towards the defence of Jewish lives and properties.The Stern Gang however, motivated more by blind hatred than patriotism, intensified their attacks on the British and later turned to massacring Arab civilians. The Jews hated the Paras and labelled them anti-Semitic.

They took to calling all Paras "Kalaniot", the hebrew word of the poppy, a red flower with a black heart. In the summer of 1947 the UN Special Committee toured Palestine eagerly supported by the Jewish Agency but boycotted by the Arabs. Their report recommended partition and this was carried by 33 votes to 13 with 10 abstentions.The decision was made and the UN washed its hands of the affair. The date set for laying down the mandate was May the 15th 1948. The final months saw the 6th Parachute Division's role change from one of peace keeping between Jews and Arabs, who were being reinforced by gangs from Iraq, Lebanon and Syria. Busloads of Jews were frequently rescued from ambush by Parachute troops.

The Car Park Murders' Taking advantage of the British reluctance to disturb the normal flow of life, the Stern Gang struck a savage blow on April 35th, no doubt as revenge for their previous setbacks. Army liberty vehicles still brought their loads of intending revellers to Tel Aviv. The vehicles parked near the sea front under the protection of a guard of eight men, who when not on sentry duty, occupied some tents that were overlooked by houses on three sides. Just after dark on the 25th the gangsters quietly entered one of these houses and held up its occupants. The men of the 5th (Scottish) Parachute Battalion on guard duty had no cause to know of this until automatic fire slashed down on them from an upper window and a grenade landed in one of the tents.

Next the gangsters were inside the tents shooting everyone inside. Seven soldiers lay dead or dying. So outraged were the comrades of the dead that they indulged in their own private, but far from lethal, reprisals on a Jewish settlement. For this they were punished.There was no punishment for any Jew in Tel Aviv. Amalgamations at this time reduced the battalions to six: 4th/6th, 5th and 7th forming the 2nd Parachute Brigade; and the 1st, 2nd/3rd and 8th/9th forming the 1st Brigade. With the withdrawal of the 2nd Brigade, the 6th Airborne Division had now only one parachute brigade under command. In Haifa, fighting took place regularly between rival populations, with the Parachute Battalion deployed between them and with the departure of the last Parachute soldiers in mid-May, Britain's brief role in Palestine's long and troubled history was over.

The bulk of Airborne troops sailed from Haifa in April while the last Airborne unit to embark was'B' Troop, 1st Airborne Squadron Royal Engineers. On arrival in the UK, the 6th Airborne Division was disbanded. In the reduction of the services to peacetime levels, it was decided that Airborne Forces should now be reduced to a single Parachute Brigade Group. In February 1948 the 2nd Brigade was designated the 16th Independent Parachute Brigade Group, with the numbers 1 and 6 perpetuating those of the 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions. The 6th Airborne Division suffered a total of 58 personnel killed and 236 wounded during their stay in Palestine. Palestina (EY), where "EY" indicates "Eretz Yisrael" (Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity under British administration, carved out of Ottoman Southern Syria after World War I.British civil administration in Palestine operated from 1920 until 1948. During its existence it was known simply as Palestine, but, in retrospect, as distinguishers, a variety of other names and descriptors including Mandatory or Mandate Palestine, also British Palestine and the British Mandate of Palestine, have been used to refer to it. During the First World War an Arab uprising and British campaign led by General Edmund Allenby, the British Empire's commander of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, drove the Turks out of the Levant, a part of which was the Sinai and Palestine Campaign.

[2] The United Kingdom had agreed in the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence that it would honour Arab independence if they revolted against the Ottomans. The two sides had different interpretations of this agreement. In the event, the UK and France divided up the area under the Sykes-Picot Agreement, an act of betrayal in the opinion of the Arabs.Further confusing the issue was the Balfour Declaration promising support for a Jewish "national home" in Palestine. After the war ended, a military administration, named Occupied Enemy Territory Administration, was established in the captured territory of the former Ottoman Syria.

The British sought legitimacy for their continued control of the region and this was achieved by obtaining a mandate from the League of Nations in June 1922. The formal objective of the League of Nations Mandate system was to administer parts of the defunct Ottoman Empire, which had been in control of the Middle East since the 16th century, until such time as they are able to stand alone. [3] The civil Mandate administration was formalized with the League of Nations' consent in 1923 under the British Mandate for Palestine, which covered two administrative areas. The land west of the Jordan River, known as Palestine, was under direct British administration until 1948, while the land east of the Jordan was a semi-autonomous region known as Transjordan, under the rule of the Hashemite family from the Hijaz, and gained independence in 1946. [4] The divergent tendencies regarding the nature and purpose of the mandate are visible already in the discussions concerning the name for this new entity.According to the Minutes of the Ninth Session of the League of Nations' Permanent Mandate Commission: " Colonel Symes explained that the country was described as "Palestine" by Europeans and as "Falestin by the Arabs. The Hebrew name for the country was the designation "Land of Israel", and the Government, to meet Jewish wishes, had agreed that the word "Palestine" in Hebrew characters should be followed in all official documents by the initials which stood for that designation. As a set-off to this, certain of the Arab politicians suggested that the country should be called "Southern Syria" in order to emphasise its close relation with another Arab State. [5] During the British Mandate period the area experienced the ascent of two major nationalist movements, one among the Jews and the other among the Arabs.

The aftermath of the Civil War and the consequent 1948 Arab-Israeli War led to the establishment of the 1949 cease-fire agreement, with partition of the former Mandatory Palestine between the newborn state of Israel with a Jewish majority, the West Bank annexed by the Jordanian Kingdom and the Arab All-Palestine Government in the Gaza Strip under the military occupation of Egypt. Contents 1 History of Palestine under the British Mandate 1.1 1930s: Arab armed insurgency 1.1.1 The Arab revolt1.1.2 Partition proposals 1.2 World War II 1.2.1 Allied and Axis activity1.2.2 Mobilization1.2.3 The Holocaust and immigration quotas1.2.4 Zionist insurgency 1.3 After World War II: the Partition Plan1.4 Termination of the Mandate 2 Politics 2.1 Name2.2 Arab community 2.2.1 Palestinian Arab leadership and national aspirations 2.3 Jewish Yishuv 2.3.1 Jewish immigration2.3.2 Jewish national home 2.4 Land ownership 2.4.1 Land ownership by district2.4.2 Land ownership by corporation2.4.3 Land ownership by type2.4.4 List of Mandatory land laws 3 Demographics 3.1 British censuses and estimations3.2 By district 4 Government and institutions5 Economy6 Education7 Gallery8 See also9 References10 Quotes11 Bibliography12 Further reading 12.1 Primary sources 13 External links History of Palestine under the British Mandate The arrival of Sir Herbert Samuel. From left to right: T. Lawrence, Emir Abdullah, Air Marshal Sir Geoffrey Salmond, Sir Herbert Samuel, Sir Wyndham Deedes and others.

This time period saw the rise of Palestinian Nationalism, Arab Christian owned Falastin newspaper was the first to warn about the perceived dangers of Zionism. 18 June 1936 issue featuring a caricature,'The Zionist Crocodile to Palestine Arabs Don't be afraid!!!

I will swallow you peacefully... In July 1920, the military administration was replaced by a civilian administration headed by a High Commissioner. [6] The first High Commissioner, Herbert Samuel, a Zionist recent cabinet minister, arrived in Palestine on 20 June 1920, to take up his appointment from 1 July. Following the arrival of the British, Muslim-Christian Associations were established in all the major towns. [citation needed] In 1919 they joined to hold the first Palestine Arab Congress in Jerusalem.

[citation needed] Its main platforms were a call for representative government and opposition to the Balfour Declaration. [citation needed] The Zionist Commission was formed in March 1918 and was active in promoting Zionist objectives in Palestine.

On 19 April 1920, elections were held for the Assembly of Representatives of the Palestinian Jewish community. [7] The Zionist Commission received official recognition in 1922 as representative of the Palestinian Jewish community.[8] One of the first actions of the newly installed civil administration in 1921 had been to grant Pinhas Rutenberg-a Jewish entrepreneur-concessions for the production and distribution of wired electricity. Rutenberg soon established an Electric Company whose shareholders were Zionist organizations, investors, and philanthropists. Palestinian-Arabs saw it as proof that the British intended to favor Zionism.

The British administration claimed that electrification would enhance the economic development of the country as a whole, while at the same time securing their commitment to facilitate a Jewish National Home through economic - rather than political - means. [9] Samuel tried to establish self-governing institutions in Palestine, as required by the mandate, but was frustrated by the refusal of the Arab leadership to co-operate with any institution which included Jewish participation. [10] When Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Kamil al-Husayni died in March 1921, High Commissioner Samuel appointed his half-brother Mohammad Amin al-Husseini to the position.

Amin al-Husseini, a member of the al-Husayni clan of Jerusalem, was an Arab nationalist and Muslim leader. As Grand Mufti, as well as the other influential positions that he held during this period, al-Husseini played a key role in violent opposition to Zionism. In 1922, al-Husseini was elected President of the Supreme Muslim Council which had been created by Samuel in December 1921.[14] In addition, he controlled the Islamic courts in Palestine. Among other functions, these courts were entrusted with the power to appoint teachers and preachers. The 1922 Palestine Order in Council[15] established a Legislative Council, which was to consist of 23 members: 12 elected, 10 appointed, and the High Commissioner. [16] Of the 12 elected members, eight were to be Muslim Arabs, two Christian Arabs and two Jews.

[17] Arabs protested against the distribution of the seats, arguing that as they constituted 88% of the population, having only 43% of the seats was unfair. [17] Elections were held in February and March 1923, but due to an Arab boycott, the results were annulled and a 12-member Advisory Council was established. [18] 1930s: Arab armed insurgency In 1930, Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam arrived in Palestine from Syria and organised and established the Black Hand, an anti-Zionist and anti-British militant organisation. He recruited and arranged military training for peasants and by 1935 he had enlisted between 200 and 800 men. The cells were equipped with bombs and firearms, which they used to kill Zionist settlers in the area, as well as engaging in a campaign of vandalism of the settlers-planted trees and British constructed rail-lines. [19] In November 1935, two of his men engaged in a firefight with a Palestine police patrol hunting fruit thieves and a policeman was killed. Following the incident, British police launched a manhunt and surrounded al-Qassam in a cave near Ya'bad. In the ensuing battle, al-Qassam was killed. [19] The Arab revolt Arab revolt against the British. Huge crowds accompanied Qassam's body to his grave in Haifa. A few months later, in April 1936, the Arab national general strike broke out. The strike lasted until October 1936, instigated by the Arab Higher Committee, headed by Amin al-Husseini. During the summer of that year, thousands of Jewish-farmed acres and orchards were destroyed, Jewish civilians were attacked and killed, and some Jewish communities, such as those in Beisan and Acre, fled to safer areas. 80 The violence abated for about a year while the British sent the Peel Commission to investigate. 87-90 During the first stages of the Arab Revolt, due to rivalry between the clans of al-Husseini and Nashashibi among the Palestinian Arabs, Raghib Nashashibi was forced to flee to Egypt after several assassination attempts ordered by Amin al-Husseini. [20] Following the Arab rejection of the Peel Commission recommendation, the revolt resumed in autumn of 1937. Over the next 18 months, the British lost control of Nablus and Hebron. British forces, supported by 6,000 armed Jewish auxiliary police, [21] suppressed the widespread riots with overwhelming force. The British officer Charles Orde Wingate (who supported a Zionist revival for religious reasons[22]) organised Special Night Squads composed of British soldiers and Jewish volunteers such as Yigal Alon, which "scored significant successes against the Arab rebels in the lower Galilee and in the Jezreel valley"Black 1991, p. 14 by conducting raids on Arab villages. 247, 249, 350 The Jewish militia Irgun used violence also against Arab civilians as "retaliatory acts", [23] attacking marketplaces and buses. By the time the revolt concluded in March 1939, more than 5,000 Arabs, 400 Jews, and 200 British had been killed and at least 15,000 Arabs were wounded. [24] The Revolt resulted in the deaths of 5,000 Palestinian Arabs and the wounding of 10,000. In total, 10% of the adult Arab male population was killed, wounded, imprisoned, or exiled.26 From 1936 to 1945, while establishing collaborative security arrangements with the Jewish Agency, the British confiscated 13,200 firearms from Arabs and 521 weapons from Jews. 845 The attacks on the Jewish population by Arabs had three lasting effects: First, they led to the formation and development of Jewish underground militias, primarily the Haganah, which were to prove decisive in 1948. Secondly, it became clear that the two communities could not be reconciled, and the idea of partition was born. However, with the advent of World War II, even this reduced immigration quota was not reached.

The White Paper policy also radicalised segments of the Jewish population, who after the war would no longer cooperate with the British. The revolt had a negative effect on Palestinian Arab leadership, social cohesion, and military capabilities and contributed to the outcome of the 1948 War because when the Palestinians faced their most fateful challenge in 1947-49, they were still suffering from the British repression of 1936-39, and were in effect without a unified leadership. Indeed, it might be argued that they were virtually without any leadership at all. 28 Partition proposals Jewish demonstration against White Paper in Jerusalem in 1939 In 1937, the Peel Commission proposed a partition between a small Jewish state, whose Arab population would have to be transferred, and an Arab state to be attached to Jordan. The proposal was rejected outright by the Arabs. The two main Jewish leaders, Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion, had convinced the Zionist Congress to approve equivocally the Peel recommendations as a basis for more negotiation. [25][26][27][28][29] In a letter to his son in October 1937, Ben-Gurion explained that partition would be a first step to "possession of the land as a whole". [30][31][32] The same sentiment was recorded by Ben-Gurion on other occasions, such as at a meeting of the Jewish Agency executive in June 1938, [33] as well as by Chaim Weizmann. This was seen by the Yishuv as betrayal of the mandatory terms, especially in light of the increasing persecution of Jews in Europe. In response, Zionists organised Aliyah Bet, a program of illegal immigration into Palestine.Lehi, a small group of extremist Zionists, staged armed attacks on British authorities in Palestine. However, the Jewish Agency, which represented the mainstream Zionist leadership, still hoped to persuade Britain to allow resumed Jewish immigration, and cooperated with Britain in World War II. World War II Allied and Axis activity Jewish Brigade headquarters under the Union Flag and Jewish flag.

On 10 June 1940, Italy declared war on the British Commonwealth and sided with Germany. Within a month, the Italians attacked Palestine from the air, bombing Tel Aviv and Haifa, [35] inflicting multiple casualties. In 1942, there was a period of great concern for the Yishuv, when the forces of German General Erwin Rommel advanced east in North Africa towards the Suez Canal and there was fear that they would conquer Palestine. This period was referred to as the two hundred days of anxiety.

This event was the direct cause for the founding, with British support, of the Palmach[36] - a highly trained regular unit belonging to Haganah (a paramilitary group which was mostly made up of reserve troops). As in most of the Arab world, there was no unanimity amongst the Palestinian Arabs as to their position regarding the combatants in World War II. A number of leaders and public figures saw an Axis victory as the likely outcome and a way of securing Palestine back from the Zionists and the British.Even though Arabs were not highly regarded by Nazi racial theory, the Nazis encouraged Arab support as a counter to British hegemony. [37] SS-Reichsfuehrer Heinrich Himmler was keen to exploit this, going so far as to enlist the aid of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Mohammad Amin al-Husseini, sending him the following telegram on 2 November 1943: To the Grand Mufti: The National Socialist movement of Greater Germany has, since its inception, inscribed upon its flag the fight against the world Jewry. It has therefore followed with particular sympathy the struggle of freedom-loving Arabs, especially in Palestine, against Jewish interlopers. In the recognition of this enemy and of the common struggle against it lies the firm foundation of the natural alliance that exists between the National Socialist Greater Germany and the freedom-loving Muslims of the whole world. Heinrich Himmler Volunteers marching on Allenby Street in Tel Aviv in favor of enlistment into the British army, 13 July 1940 The Mufti al-Husseini would spend the rest of the war in Nazi Germany and the occupied areas in Europe.

[citation needed] Mobilization On 3 July 1944, the British government consented to the establishment of a Jewish Brigade, with hand-picked Jewish and also non-Jewish senior officers. On 20 September 1944, an official communiqué by the War Office announced the formation of the Jewish Brigade Group of the British Army. The Jewish brigade then was stationed in Tarvisio, near the border triangle of Italy, Yugoslavia, and Austria, where it played a key role in the Berihah's efforts to help Jews escape Europe for Palestine, a role many of its members would continue after the brigade was disbanded. Among its projects was the education and care of the Selvino children. Later, veterans of the Jewish Brigade became key participants of the new State of Israel's Israel Defense Forces.

Australian soldiers in Tel Aviv in 1942 From Palestine Regiment, two platoons, one Jewish, under the command of Brigadier Ernest Benjamin, and another Arab were sent to join allied forces on the Italian Front, having taken part of final offensive there. Besides Jews and Arabs from Palestine, in total by mid-1944 the British had assembled a multiethnic force consisting of volunteer European Jewish refugees (from German-occupied countries), Yemenite Jews and Abyssinian Jews. [38] The Holocaust and immigration quotas In 1939, as a consequence of the White Paper of 1939, the British reduced the number of immigrants allowed into Palestine.

World War II and the Holocaust started shortly thereafter and once the 15,000 annual quota was exceeded, Jews fleeing Nazi persecution were interned in detention camps or deported to places such as Mauritius. [39] Starting in 1939, a clandestine immigration effort called Aliya Bet was spearheaded by an organisation called Mossad LeAliyah Bet. The Royal Navy intercepted many of the vessels; others were unseaworthy and were wrecked; a Haganah bomb sunk the SS Patria, killing 267 people; two more were sunk by Soviet submarines. The motor schooner Struma was torpedoed and sunk in the Black Sea by a Soviet submarine in February 1942 with the loss of nearly 800 lives. [40] The last refugee boats to try to reach Palestine during the war were the Bulbul, Mefküre and Morina in August 1944. A Soviet submarine sank the motor schooner Mefküre by torpedo and shellfire and machine-gunned survivors in the water, [41] killing between 300 and 400 refugees. [42] Illegal immigration resumed after World War II. After the war 250,000 Jewish refugees were stranded in displaced persons (DP) camps in Europe. Despite the pressure of world opinion, in particular the repeated requests of US President Harry S. Truman and the recommendations of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry that 100,000 Jews be immediately granted entry to Palestine, the British maintained the ban on immigration. Zionist insurgency The Jewish Lehi (Fighters for the Freedom of Israel) and Irgun (National Military Organization) movements initiated violent uprisings against the British Mandate in 1940, in the former case, and in 1939, briefly, and 1944, for longer and on a larger scale, in the latter. On 6 November 1944, Eliyahu Hakim and Eliyahu Bet Zuri (members of Lehi) assassinated Lord Moyne in Cairo. Moyne was the British Minister of State for the Middle East and the assassination is said by some to have turned British Prime Minister Winston Churchill against the Zionist cause. After the assassination of Lord Moyne, the Haganah kidnapped, interrogated, and turned over to the British many members of the Irgun ("The Hunting Season"), and the Jewish Agency Executive decided on a series of measures against "terrorist organizations" in Palestine. [43] Irgun ordered its members not to resist or retaliate with violence, so as to prevent a civil war. The three main Jewish underground forces later united to form the Jewish Resistance Movement and carry out several attacks and bombings against the British administration. In 1946, the Irgun blew up the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, the headquarters of the British administration, killing 92 people. Following the bombing, the British Government began interning illegal Jewish immigrants in Cyprus.In 1948 the Lehi assassinated the UN mediator Count Bernadotte in Jerusalem. Yitzak Shamir, future prime minister of Israel was one of the conspirators. Jerusalem on VE Day, 8 May 1945 The negative publicity resulting from the situation in Palestine caused the Mandate to become widely unpopular in Britain, and caused the United States Congress to delay granting the British vital loans for reconstruction.

The British Labour party had promised before its election to allow mass Jewish migration into Palestine but reneged on this promise once in office. Anti-British Jewish militancy increased and the situation required the presence of over 100,000 British troops in the country. Following the Acre Prison Break and the retaliatory hanging of British Sergeants by the Irgun, the British announced their desire to terminate the mandate and withdraw by no later than the beginning of August 1948. [44] After World War II: the Partition Plan The UN Partition Plan. In April, the Committee reported that its members had arrived at a unanimous decision. The Committee approved the American recommendation of the immediate acceptance of 100,000 Jewish refugees from Europe into Palestine. It also recommended that there be no Arab, and no Jewish State. The Committee stated that in order to dispose, once and for all, of the exclusive claims of Jews and Arabs to Palestine, we regard it as essential that a clear statement of principle should be made that Jew shall not dominate Arab and Arab shall not dominate Jew in Palestine. President Harry S Truman angered the British Government by issuing a statement supporting the 100,000 refugees but refusing to acknowledge the rest of the committee's findings.Britain had asked for U. S assistance in implementing the recommendations. War Department had said earlier that to assist Britain in maintaining order against an Arab revolt, an open-ended U. Commitment of 300,000 troops would be necessary.

The immediate admission of 100,000 new Jewish immigrants would almost certainly have provoked an Arab uprising. [45] These events were the decisive factors that forced Britain to announce their desire to terminate the Palestine Mandate and place the Question of Palestine before the United Nations, the successor to the League of Nations.

The UN created UNSCOP (the UN Special Committee on Palestine) on 15 May 1947, with representatives from 11 countries. UNSCOP conducted hearings and made a general survey of the situation in Palestine, and issued its report on 31 August. Seven members (Canada, Czechoslovakia, Guatemala, Netherlands, Peru, Sweden, and Uruguay) recommended the creation of independent Arab and Jewish states, with Jerusalem to be placed under international administration.Three members (India, Iran, and Yugoslavia) supported the creation of a single federal state containing both Jewish and Arab constituent states. On 29 November, the UN General Assembly, voting 33 to 13, with 10 abstentions, adopted a resolution recommending the adoption and implementation of the Plan of Partition with Economic Union as Resolution 181 (II).

[46] while making some adjustments to the boundaries between the two states proposed by it. The division was to take effect on the date of British withdrawal.

The partition plan required that the proposed states grant full civil rights to all people within their borders, regardless of race, religion or gender. It is important to note that the UN General Assembly is only granted the power to make recommendations, therefore, UNGAR 181 was not legally binding. And the Soviet Union supported the resolution. Haiti, Liberia, and the Philippines changed their votes at the last moment after concerted pressure from the U. [48][49][50] The five members of the Arab League, who were voting members at the time, voted against the Plan. The Jewish Agency, which was the Jewish state-in-formation, accepted the plan, and nearly all the Jews in Palestine rejoiced at the news. Israeli history books mention 29 November as the most important date in the creation of Israel as it refers to UNGA 181 of 1947 Partition of the Mandate of Palestine into two states and whereof Israel's Proclamation of Independence refers to UNGA 181 as its source of sovereignty in Ph's 9 & 15.[citation needed] The partition plan was rejected out of hand by Palestinian Arab leadership and by most of the Arab population. [qt 1][qt 2] Meeting in Cairo on November and December 1947, the Arab League then adopted a series of resolutions endorsing a military solution to the conflict. Britain announced that it would accept the partition plan, but refused to enforce it, arguing it was not accepted by the Arabs. Britain also refused to share the administration of Palestine with the UN Palestine Commission during the transitional period.

In September 1947, the British government announced that the Mandate for Palestine would end at midnight on 14 May 1948. [51][52][53] Some Jewish organisations also opposed the proposal. Irgun leader Menachem Begin announced, The partition of the Homeland is illegal. It will never be recognized. The signature by institutions and individuals of the partition agreement is invalid.It will not bind the Jewish people. Jerusalem was and will forever be our capital. Eretz Israel will be restored to the people of Israel. [54] These views were publicly rejected by the majority of the nascent Jewish state. [citation needed] Termination of the Mandate British leaving Haifa in 1948 When the UK announced the independence of Transjordan in 1946, the final Assembly of the League of Nations and the General Assembly both adopted resolutions welcoming the news.

[55] However, the Jewish Agency and many legal scholars raised objections. [citation needed] The Jewish Agency said that Transjordan was an integral part of Palestine, and that according to Article 80 of the UN Charter, the Jewish people had a secured interest in its territory. [56] During the General Assembly deliberations on Palestine, there were suggestions that it would be desirable to incorporate part of Transjordan's territory into the proposed Jewish state.

A few days before the adoption of Resolution 181 (II) on 29 November 1947, U. Secretary of State Marshall noted frequent references had been made by the Ad Hoc Committee regarding the desirability of the Jewish State having both the Negev and an outlet to the Red Sea and the Port of Aqaba. [57] According to John Snetsinger, Chaim Weizmann visited President Truman on 19 November 1947 and said it was imperative that the Negev and Port of Aqaba be under Jewish control and that they be included in the Jewish state. [58] Truman telephoned the US delegation to the UN and told them he supported Weizmann's position.

[59] The British had notified the U. Of their intent to terminate the mandate not later than 1 August 1948. [60][61] However, early in 1948, the United Kingdom announced its firm intention to end its mandate in Palestine on 14 May.

In response, President Harry S Truman made a statement on 25 March proposing UN trusteeship rather than partition, stating that unfortunately, it has become clear that the partition plan cannot be carried out at this time by peaceful means... Unless emergency action is taken, there will be no public authority in Palestine on that date capable of preserving law and order. Violence and bloodshed will descend upon the Holy Land. Large-scale fighting among the people of that country will be the inevitable result.[62] Hoisting of the Yishuv flag in Tel Aviv, 1 January 1948 The Jewish Leadership, led by future Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, declared the establishment of a Jewish State in Eretz-Israel, to be known as the State of Israel, [63] on the afternoon of Friday, 14 May 1948 (5 Iyar 5708 in the Hebrew calendar), to come into force at midnight of that day. [64][65][66] On the same day, the Provisional Government of Israel asked the US Government for recognition, on the frontiers specified in the UN Plan for Partition. [67] The United States immediately replied, recognizing the provisional government as the de facto authority.

[68] Israel was also quickly recognised by the Soviet Union[citation needed] and many other countries, [citation needed] but not by the surrounding Arab states. At the same time that the state of Israel was being declared Jewish paramilitary forces took up occupation of the evacuated British military installations in the country. As the mandate era came to an end, radical Jewish forces, from whose actions the Haganah distanced themselves, began to clear Palestinian Arab communities in the area which would become Israel. [citation needed] Over the next few days, approximately 700 Lebanese, 1,876 Syrian, 4,000 Iraqi, 2,800 Egyptian troops crossed over the borders and into Palestine (see 1948 Arab-Israeli War).[69] Around 4,500 Transjordanian troops, commanded partly by 38 British officers who had resigned their commissions in the British army only weeks earlier, including overall commander, General John Bagot Glubb, invaded the Corpus separatum region encompassing Jerusalem and its environs (in response to the Haganah's Operation Kilshon[70]) and moved into areas designated as part of the Arab state by the UN partition plan. And Hebrew; the latter includes the acronym???

For Eretz Yisrael (Land of Israel). The name given to the Mandate's territory was "Palestine", in accordance with European traditions.

[citation needed] The term Palestine was coined in the Western culture from the name of Palaestina province of the Roman (Syria-Palaestina) and later Byzantine Empire (Palaestina Prima and Palaestina Secunda). [citation needed] The Mandate charter stipulated that Mandatory Palestine would have three official languages, namely English, Arabic and Hebrew. In 1926, the British authorities formally decided to use the traditional Arabic and Hebrew equivalents to the English name, i. The Jewish leadership proposed that the proper Hebrew name should be? The final compromise was to add the initials of the Hebrew proposed name, Alef-Yud, within parenthesis???

, whenever the Mandate's name was mentioned in Hebrew in official documents. The Arab leadership saw this compromise as a violation of the mandate terms.Some Arab politicians suggested that there should be a similar Arabic concession, such as "Southern Syria"????? The British authorities rejected this proposal.

[71] Arab community Front cover Biographical pages Passports from the British Mandate era. The resolution of the San Remo Conference contained a safeguarding clause for the existing rights of the non-Jewish communities. The conference accepted the terms of the Mandate with reference to Palestine, on the understanding that there was inserted in the process-verbal a legal undertaking by the Mandatory Power that it would not involve the surrender of the rights hitherto enjoyed by the non-Jewish communities in Palestine. [72] The draft mandates for Mesopotamia and Palestine, and all of the post-war peace treaties contained clauses for the protection of religious groups and minorities. The mandates invoked the compulsory jurisdiction of the Permanent Court of International Justice in the event of any disputes. [73] Article 62 (LXII) of the Treaty of Berlin, 13 July 1878[74] dealt with religious freedom and civil and political rights in all parts of the Ottoman Empire. [75] The guarantees have frequently been referred to as "religious rights" or "minority rights".However, the guarantees included a prohibition against discrimination in civil and political matters. Difference of religion could not be alleged against any person as a ground for exclusion or incapacity in matters relating to the enjoyment of civil or political rights, admission to public employments, functions, and honours, or the exercise of the various professions and industries, in any locality whatsoever.

A legal analysis performed by the International Court of Justice noted that the Covenant of the League of Nations had provisionally recognised the communities of Palestine as independent nations. The mandate simply marked a transitory period, with the aim and object of leading the mandated territory to become an independent self-governing State. [76] Judge Higgins explained that the Palestinian people are entitled to their territory, to exercise self-determination, and to have their own State.[77] The Court said that specific guarantees regarding freedom of movement and access to the Holy Sites contained in the Treaty of Berlin (1878) had been preserved under the terms of the Palestine Mandate and a chapter of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine. [78] According to historian Rashid Khalidi, the mandate ignored the political rights of the Arabs. [79] The Arab leadership repeatedly pressed the British to grant them national and political rights, such as representative government, over Jewish national and political rights in the remaining 23% of the Mandate of Palestine which the British had set aside for a Jewish homeland. The Arabs reminded the British of President Wilson's Fourteen Points and British promises during the First World War. The British however made acceptance of the terms of the mandate a precondition for any change in the constitutional position of the Arabs.

A legislative council was proposed in The Palestine Order in Council, of 1922 which implemented the terms of the mandate. It stated that: No Ordinance shall be passed which shall be in any way repugnant to or inconsistent with the provisions of the Mandate. " For the Arabs, this was unacceptable, as they felt that this would be "self murder.

[80] As a result, the Arabs boycotted the elections to the Council held in 1923, which were subsequently annulled. [81] During the whole interwar period, the British, appealing to the terms of the mandate, which they had designed themselves, rejected the principle of majority rule or any other measure that would give an Arab majority control over the government of Palestine. [82] The terms of the mandate required the establishment of self-governing institutions in both Palestine and Transjordan. In 1947, Foreign Secretary Bevin admitted that during the previous twenty-five years the British had done their best to further the legitimate aspirations of the Jewish communities without prejudicing the interests of the Arabs, but had failed to "secure the development of self-governing institutions" in accordance with the terms of the Mandate.

[83] Palestinian Arab leadership and national aspirations Main articles: Palestinian Nationalism and Arab nationalism Under the British Mandate, the office of "Mufti of Jerusalem", traditionally limited in authority and geographical scope, was refashioned into that of "Grand Mufti of Palestine". 63 In dealings with the Palestinian Arabs, the British negotiated with the elite rather than the middle or lower classes. 52 They chose Hajj Amin al-Husseini to become Grand Mufti, although he was young and had received the fewest votes from Jerusalem's Islamic leaders. 56-57 One of the mufti's rivals, Raghib Bey al-Nashashibi, had already been appointed mayor of Jerusalem in 1920, replacing Musa Kazim, whom the British removed after the Nabi Musa riots of 1920, Khalidi 2006, pp. 127-144 during which he exhorted the crowd to give their blood for Palestine.

112 During the entire Mandate period, but especially during the latter half, the rivalry between the mufti and al-Nashashibi dominated Palestinian politics. Khalidi ascribes the failure of the Palestinian leaders to enroll mass support, because of their experiences during the Ottoman Empire period, as they were then part of the ruling elite and accustomed to their commands being obeyed. The idea of mobilising the masses was thoroughly alien to them. 81 There had already been rioting and attacks on and massacres of Jews in 1921 and 1929.

During the 1930s, Palestinian Arab popular discontent with Jewish immigration grew. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, several factions of Palestinian society, especially from the younger generation, became impatient with the internecine divisions and ineffectiveness of the Palestinian elite and engaged in grass-roots anti-British and anti-Zionist activism, organised by groups such as the Young Men's Muslim Association. There was also support for the radical nationalist Independence Party (Hizb al-Istiqlal), which called for a boycott of the British in the manner of the Indian Congress Party.Some took to the hills to fight the British and the Jews. Most of these initiatives were contained and defeated by notables in the pay of the Mandatory Administration, particularly the mufti and his cousin Jamal al-Husseini.

A six-month general strike in 1936 marked the start of the great Arab Revolt. 87-90 Jewish Yishuv Main article: History of Zionism See also: History of the State of Israel The conquest of the Ottoman Syria by the British forces in 1917, found a mixed community in the region, with Palestine, the southern part of the Ottoman Syria, containing a mixed population of Muslims, Christians, Jews and Druze. In this period, the Jewish community (Yishuv) in Palestine was composed of traditional Jewish communities in cities (the Old Yishuv), which had existed for centuries, and the newly established agricultural Zionist communities (the New Yishuv), established since the 1870s.

With the establishment of the Mandate, the Jewish community in Palestine formed the Zionist Commission to represent its interests. In 1929, the Jewish Agency for Palestine took over from the Zionist Commission its representative functions and administration of the Jewish community. During the Mandate period, the Jewish Agency was a quasi-governmental organisation that served the administrative needs of the Jewish community. Its leadership was elected by Jews from all over the world by proportional representation. It ran schools and hospitals, and formed the Haganah.

The British authorities offered to create a similar Arab Agency but this offer was rejected by Arab leaders. [85] In response to numerous Arab attacks on Jewish communities, the Haganah, a Jewish paramilitary organisation, was formed on 15 June 1920 to defend Jewish residents.

Beginning in 1936, Jewish groups such as Etzel (Irgun) and Lehi (Stern Gang) conducted campaigns of violence against British military and Arab targets. Jewish immigration During the Mandate, the Yishuv or Jewish community in Palestine, grew from one-sixth to almost one-third of the population.According to official records, 367,845 Jews and 33,304 non-Jews immigrated legally between 1920 and 1945. [86] It was estimated that another 50-60,000 Jews and a marginal number of Arabs, the latter mostly on a seasonal basis, immigrated illegally during this period. [87] Immigration accounted for most of the increase of Jewish population, while the non-Jewish population increase was largely natural.

[88] Initially, Jewish immigration to Palestine met little opposition from the Palestinian Arabs. However, as anti-Semitism grew in Europe during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Jewish immigration (mostly from Europe) to Palestine began to increase markedly.

Combined with the growth of Arab nationalism in the region and increasing anti-Jewish sentiments the growth of Jewish population created much Arab resentment. The British government placed limitations on Jewish immigration to Palestine.

These quotas were controversial, particularly in the latter years of British rule, and both Arabs and Jews disliked the policy, each for their own reasons. Jewish immigrants were to be afforded Palestinian citizenship: Article 7. The Administration of Palestine shall be responsible for enacting a nationality law.There shall be included in this law provisions framed so as to facilitate the acquisition of Palestinian citizenship by Jews who take up their permanent residence in Palestine. He also represented the Zionist Organization at the Paris Peace Conference.

The object of Zionism is to establish for the Jewish people a home in Palestine secured by public law. It has been said and is still being obstinately repeated by anti-Zionists again and again, that Zionism aims at the creation of an independent "Jewish State" But this is fallacious. The "Jewish State" was never part of the Zionist programme. The Jewish State was the title of Herzl's first pamphlet, which had the supreme merit of forcing people to think. This pamphlet was followed by the first Zionist Congress, which accepted the Basle programme - the only programme in existence.Nahum Sokolow, History of Zionism[90] One of the objectives of British administration was to give effect to the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which was also set out in the preamble of the mandate, as follows: Whereas the Principal Allied Powers have also agreed that the Mandatory should be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2nd, 1917, by the Government of His Britannic Majesty, and adopted by the said Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing should be done which might prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country. [91] The United Nations Special Committee on Palestine said the Jewish National Home, which derived from the formulation of Zionist aspirations in the 1897 Basle program has provoked many discussions concerning its meaning, scope and legal character, especially since it had no known legal connotation and there are no precedents in international law for its interpretation. It was used in the Balfour Declaration and in the Mandate, both of which promised the establishment of a "Jewish National Home" without, however, defining its meaning. A statement on "British Policy in Palestine, " issued on 3 June 1922 by the Colonial Office, placed a restrictive construction upon the Balfour Declaration.

The Committee noted that the construction, which restricted considerably the scope of the National Home, was made prior to the confirmation of the Mandate by the Council of the League of Nations and was formally accepted at the time by the Executive of the Zionist Organization. [92] In March 1930, Lord Passfield, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, had written a Cabinet Paper[93] which said: In the Balfour Declaration there is no suggestion that the Jews should be accorded a special or favoured position in Palestine as compared with the Arab inhabitants of the country, or that the claims of Palestinians to enjoy self-government (subject to the rendering of administrative advice and assistance by a Mandatory as foreshadowed in Article XXII of the Covenant) should be curtailed in order to facilitate the establishment in Palestine of a National Home for the Jewish people. Zionist leaders have not concealed and do not conceal their opposition to the grant of any measure of self-government to the people of Palestine either now or for many years to come.

Some of them even go so far as to claim that that provision of Article 2 of the Mandate constitutes a bar to compliance with the demand of the Arabs for any measure of self-government. In view of the provisions of Article XXII of the Covenant and of the promises made to the Arabs on several occasions that claim is inadmissible. The League of Nations Permanent Mandates Commission took the position that the Mandate contained a dual obligation. In 1932 the Mandates Commission questioned the representative of the Mandatory on the demands made by the Arab population regarding the establishment of self-governing institutions, in accordance with various articles of the mandate, and in particular Article 2.The Chairman noted that under the terms of the same article, the mandatory Power had long since set up the Jewish National Home. [94] In 1937, the Peel Commission, a British Royal Commission headed by Earl Peel, proposed solving the Arab-Jewish conflict by partitioning Palestine into two states. [25][26][27][95] The US Consul General at Jerusalem told the State Department that the Mufti had refused the principle of partition and declined to consider it.

The Consul said that the Emir Abdullah urged acceptance on the ground that realities must be faced, but wanted modification of the proposed boundaries and Arab administrations in the neutral enclave. The Consul also noted that Nashashibi sidestepped the principle, but was willing to negotiate for favourable modifications.[96] A collection of private correspondence published by David Ben Gurion contained a letter written in 1937 which explained that he was in favour of partition because he didn't envision a partial Jewish state as the end of the process. Ben Gurion wrote What we want is not that the country be united and whole, but that the united and whole country be Jewish. He explained that a first-class Jewish army would permit Zionists to settle in the rest of the country with or without the consent of the Arabs.